Roads of Natchez

This project was created in Winter 2023 by Isabella Durgin at UCLA.

Special thanks to Anne Gilliland, Marianna Hovhannisyan, UCLA Library Special Collections, UCLA HumSpace, Mississippi Department of Archives & History, Digital Collections at the University of Southern Mississippi, and many more.

I was born and raised in Meridian, a town in central Mississippi near the border of Alabama. I’ve always felt a responsibility to know about home, particularly as I am a white individual whose parents moved from elsewhere in the country. I do not have the familial ties to the state’s history, but I am complicit in the systems of dispossession that were the results of colonialism and enslavement at the hands of white settlers. This archival and mapping project is therefore viewed through my lens, and I acknowledge that this project is more personal and does not seek to make broad, overarching claims.

For this project, I began by wanting to explore land relations in a different part of the state. My town is full of pine trees, red clay, railroads, and remnants of industry. Natchez, on the other hand, is along the Mississippi River, giving it fertile soil on which the plantation agriculture system could be built, and has since leaned into its fabricated antebellum allure. Roads have significance as both avenues for movement and locales of land relations. The Natchez Trace Parkway, a route that stretches from Natchez to Nashville, is therefore my conceptual starting point. The Trace does not capture a more full sense of Black history, however. I therefore include Natchez’ Saint Catherine Street as a more robust exploration of the African American community in Natchez, since Black history is Mississippi history.

This project relies upon maps as its framework for thinking through paths and land. This foundation is inherently colonial. For example, the object on the left is from a survey for the Natchez Trace Parkway. It attempts to document the various Native American communities whose ancestral lands are in this region, but places a colonial border around them, constricting the existing community and land to the arbitrary concept of Mississippi––itself a word derived from Indigenous roots––under the Mississippi Territory.

Roads of Natchez begins with this acknowledgement that my home is on the stolen lands of the Choctaw, Chickasaw, Natchez, and Muscogee (Creek) peoples (as well as others), and that attempts to map Mississippi will, in some part, contribute to the erasure of the land’s Indigeneity. For the interactive map I created, I used the National Tribal Geographic Information Support Center in an attempt to rectify my settler perspective.

There are two ways to explore this project: with archival materials & an interactive map. The two were designed to complete the other. For a better experience, please explore sections 1-5 of the map as you move through the images below.

Where the Natchez Trace Begins

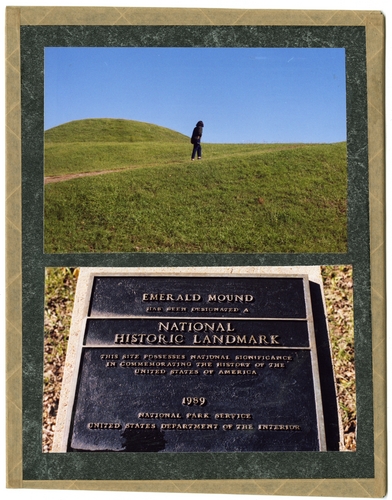

The Natchez Trace is today a parkway operated by the National Park Service. Prior, though, the road was a network of routes that emerged from the landscape and the movement of the Natchez people. The Natchez Nation built mounds, as did many other Indigenous societies, and the Trace moves alongside several of them

Emerald Mound (above) is the original starting point of the Old Trace, and is evidence of the Natchez Nation emphasizing the Trace as the route of choice to move northward over the nearby Mississippi River. 242 miles away is Bynum Mounds (left).

The Old Trace & National Park Service

Connection to SEPARATION

By the time the Trace was being used by colonial settlers, the Natchez community was deemed to have been erased in the 18th century. However, they still persist as an active, but diasporic people with ties to the Mvskoke (Muscogee Nation) and the Cherokee Nation.

Since the Old Trace is a part of the Native Mississippi landscape as firstly a travel route for people and trade across the regional Native American communities, we can find an emphasis on connection.

But, by the time it had received federal postal road status in the early 19th century, the Trace had become a route of transportation for white settlers of Mississippi.

It transported colonialism through the imposition of new land relations and a new economic system (systems of fragmentation) in the form of those deemed “people” (white settlers) and those deemed “economic goods.” In this latter category were enslaved people of African descent who were forcibly marching on the Trace at a similar historical moment as the Native American communities alongside the road were forcibly removed.

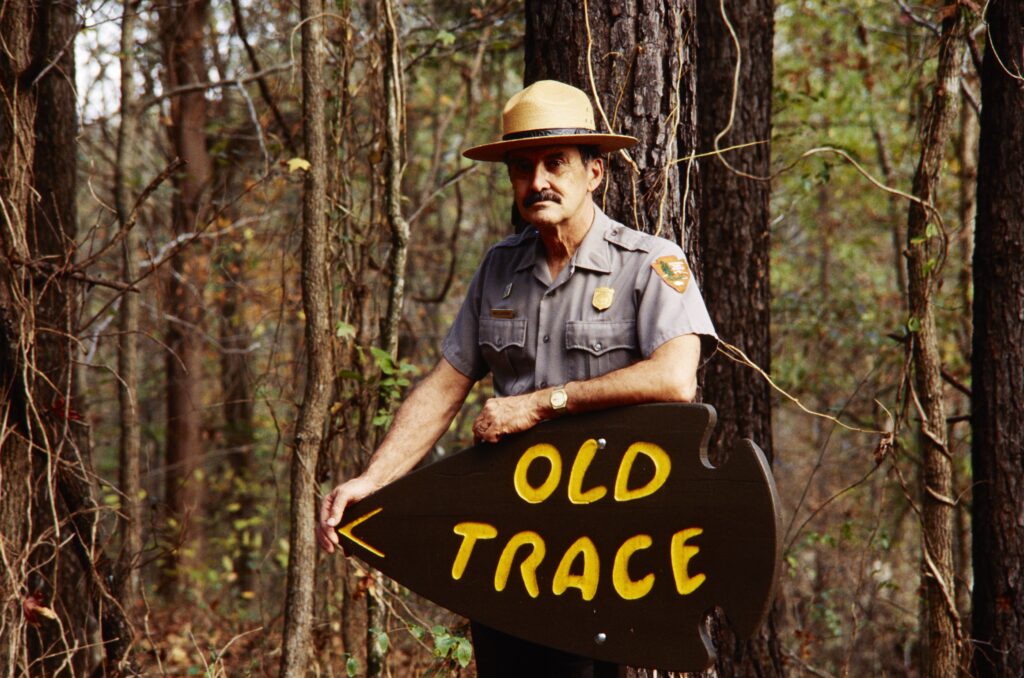

National Park Service began overseeing the route as the Natchez Trace Parkway in the 1930s, and the route became a place of recreation. This was, and is, a half-hearted attempt to restore the travel-connection relationship the land once held. Although it is not primarily a place of transportation-fragmentation anymore, NPS cannot fully tap back into the land’s original significance because it, as a proxy of the federal government, is complicit in displacing the peoples who lived along the route and formed that path.

The recreational enjoyment of Trace history also veers on tokenizing—as it depicts locations on the Trace like Bynum and the Native American societies that built mounds as primitive—or at the very least artificial. Moreover, the Trace has historically captured the white imagination as a “dangerous,” “bloody” place when, in reality, it most likely was not.

Natchez & the White Imaginary

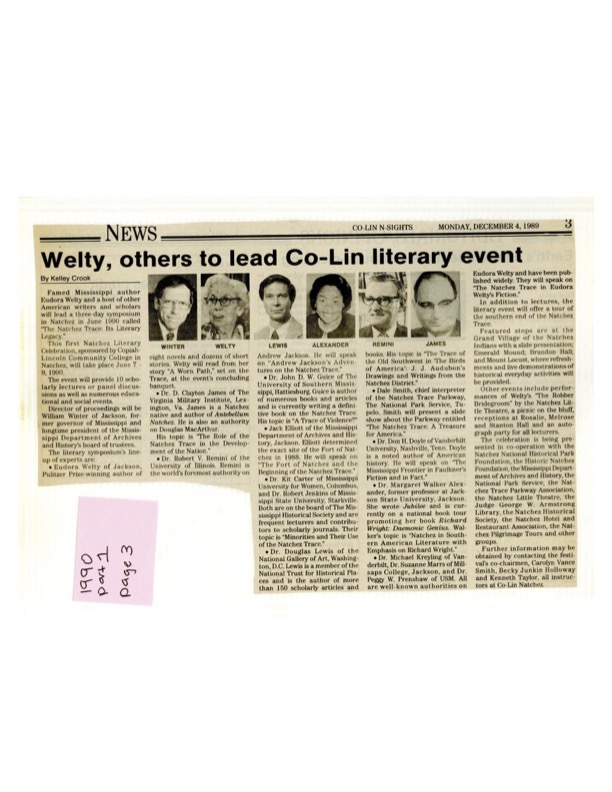

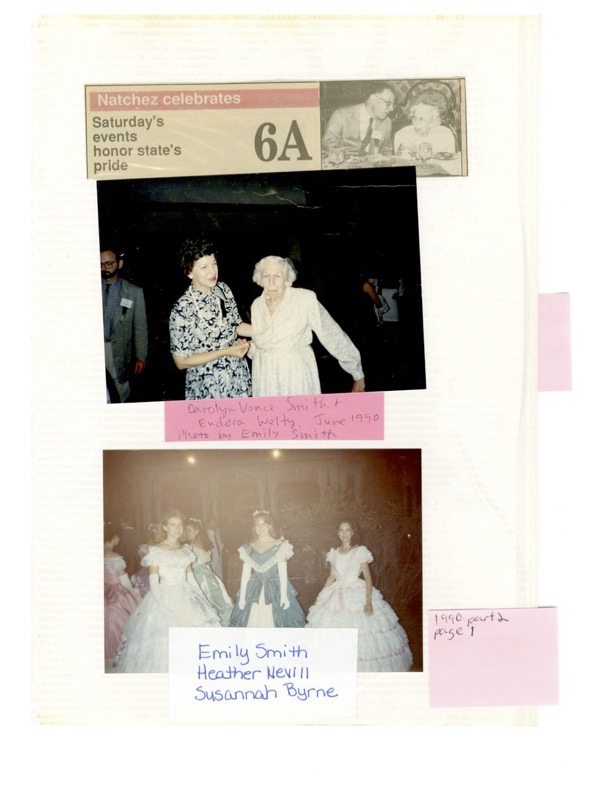

Natchez Literary Celebration

In order to be as transparent as possible about my sources, I want to briefly touch on the first annual Natchez Literary Celebration. This event, which occurred in June 1990, featured scholars and famed Mississippi author Eudora Welty (above) to speak about Natchez. All of those speeches, except for Eudora Welty’s, were then printed in a special edition of The Southern Quarterly, a journal run by the University of Southern Mississippi in Hattiesburg, the following summer. Perhaps unsurprisingly after our conversation on the NPS and the Trace, many of these talks centered around the Natchez Trace. They were nearly all thoroughly researched, factually grounded, and critical of the mythos of the Trace that demonized the Choctaw people, erased the Natchez people, and excluded the Black community. However, the setting of this event and its overwhelming of whiteness and antebellum aesthetics (center) cannot be ignored, and thus I have included the above materials.

Saint Catherine Street

Please move to Section 6 and explore the three icons on the road.

Professor Brumfield

The Black history of Natchez is partially obscured, as there is an abundance of archival silences in this space that relies so heavily on its pre-Civil War history and aesthetics.

Professor George Washington Brumfield (right) taught for more than 25 years in Natchez’ segregated schools beginning in the 1890s, and in 1925 a segregated school was completed and named after him. The Brumfield School still stands on Saint Catherine Street, despite being closed in 1990, and is part of a series of markers around Natchez launched for 2023 Black History Month.

Several other of these markers are on Saint Catherine Street:

- Zion Chapel AME, where Brumfield worked at the turn of the 20th century and a few decades earlier (1860s) had Hiram Revels, the first African American to serve in Congress, as its pastor.

- Forks in the Road was the second-busiest markets for slavery in the United States in the mid-19th century, where Franklin and Armfield, the largest slave trading firm in the South, ran one of its two main depots (other was New Orleans, just down the river).

Oral History with Mamie Mazique

This 1996 oral history captures the voice and lived experiences of Natchez inhabitant Mamie Mazique, a Black educator who attended the Brumfield School. This interview offers a rich discussion of education during her lifetime in Natchez and Mississippi. For those that prefer to read the interview, there is a transcript available, but there is an incredible sense of connection to Mamie Mazique and Southerness established in listening to the whole interview.

She also discusses her older sister, Mosana Green, who ran a restaurant and business called the White House Café—or the “White House,” as Mamie Mazique calls it—where civil rights leaders from across the state and country met for NAACP organizing and to gather. In 1965, the White House Café and its phone number were listed in SNCC documents as an SNCC Office, along with three other locations in Natchez–one of which a funeral home. (As of my current research, though, I have not been able to track down more information about the White House Cafè.)

Mamie Mazique herself was fully engaged in this community and their fight to desegregate the city, and was a founding member of Natchez’ NAACP chapter. Three months before this interview, she helped to found the Adams Jefferson Improvement Corporation, now the AJFC Community Action Agency, which ran a Head Start program.

It is because of Mamie Mazique, Professor Brumfield, and other leaders of the Black Natchez community across the decades that the story Natchez tells is changed. The antebellum Deep South cannot and will not be our future. Mississippi’s narrative is changing to reflect all the histories and communities that were buried by the white settler and far-right narrative, but we can change that when we seek alternative voices out, ones that match the actual people of Mississippi. I am proud of my Mississippi heritage because of these individuals, and I will continue to work to be a part of uplifting voices from the past and present.

Bibliography

“About Nvculke Wvlt Tvluen Mvnv Pumpeyv.” Natchez Nation, http://www.natcheznation.com/About-Us.html.

“African American Public Education: Natchez Trails.” The Historical Marker Database, 29 March 2018, https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=115615.

Barnett, James F. “The Natchez Indians and the Trace.” Southern Quarterly, vol. 29, no. 4, Summer 1991, https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/natchez-indians-trace/docview/1416160773/se-2.

Barnett, Jim. “The Forks of the Road Slave Market at Natchez.” Mississippi History Now, February 2003, https://www.mshistorynow.mdah.ms.gov/issue/the-forks-of-the-road-slave-market-at-natchez.

Ben, Cyrus. “Welcome from the Tribal Chief of the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians.” Choctaw.org, https://www.choctaw.org/.

Block, Melissa and Elissa Nadworny. “Here’s What’s Become Of A Historic All-Black Town In The Mississippi Delta.” NPR, 8 March 2017, https://www.npr.org/2017/03/08/515814287/heres-whats-become-of-a-historic-all-black-town-in-the-mississippi-delta.

“Brumfield High School, Natchez, Mississippi.” Historic Structures, 31 July 2022, https://www.historic-structures.com/ms/natchez/brumfield_school.php.

Falk, Susan T. “Remembering Dixie: The Battle to Control Historical Memory in Natchez, Mississippi, 1865-1941.” University Press of Mississippi, 23 August 2019, https://doi.org/10.14325/mississippi/9781496824400.001.0001.

Guice, John D W. “A Trace of Violence?” Southern Quarterly, vol. 29, no. 4, Summer 1991, https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/trace-violence/docview/1416160249/se-2.

James, D Clayton. “The Role of the Natchez Trace in the Development of the Nation.” Southern Quarterly, vol. 29, no. 4, Summer 1991, https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/role-natchez-trace-development-nation/docview/1416160546/se-2.

Jenkins, Robert L. “African-Americans on the Natchez Trace, 1800-1865.”Southern Quarterly, vol. 29, no. 4, Summer 1991, https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/african-americans-on-natchez-trace-1800-1865/docview/1416161715/se-2.

Mickens, Cassandra. “Mamie Lee Mazique named 2010 Citizen of the Year.” The Natchez Democrat, 28 February 2010, https://www.natchezdemocrat.com/2010/02/28/mamie-lee-mazique-named-2010-citizen-of-the-year/.

“National Tribal Geographic Information Support Center.” https://tribalgis.maps.arcgis.com/home/index.html.

Riley, Harriet. “A Place Apart: Mound Bayou.” MississippiFolkLife, 23 October 2020, https://mississippifolklife.org/articles/a-place-apart-mound-bayou.

Senate Historical Office. “Senate Stories | Hiram Revels: First African American Senator.” 25 February 2020, https://www.senate.gov/artandhistory/senate-stories/First-African-American-Senator.htm.

Shelton, Lindsey. “Mazique remembered for quiet, strong leadership.” The Natchez Democrat, 21 April 2017, https://www.natchezdemocrat.com/2017/04/21/mazique-remembered-for-quiet-strong-leadership/.

“SNCC Offices in the South, February, 1965,” Page 3, https://www.crmvet.org/docs/6502_sncc_offices.pdf.

Staff Reports. “Mazique retires after 40-year devotion to children.” The Natchez Democrat, 19 October 2006, https://www.natchezdemocrat.com/2006/10/19/mazique-retires-after-40-year-devotion-to-children/.

Staff Reports. “New historic markers unveiled to tell whole story of Natchez, honor contributions of African Americans.” The Natchez Democrat, 2 February 2023, https://www.natchezdemocrat.com/2023/02/02/new-historic-markers-unveiled-to-tell-whole-story-of-natchez-honor-contributions-of-african-americans/.

“Visit Forks in the Road.” National Park Service, https://www.nps.gov/thingstodo/about-forks-of-the-road.htm.